Employee monitoring: to track or not to track?

As anyone who has ever worked in the corporate world knows, it’s easy to clock up a 9-5 day and get absolutely nothing done. Before computers were the office norm, you could probably stare into cubicle abyss all day, pretending to read memos. Now that a lot of ‘knowledge economy’ work is screen-based, it’s easy to track. You might be able to flick between Facebook and Powerpoint when your manager does a drive by. But you can’t hide your idleness from your computer. It know’s what you’re doing.

Employee monitoring is nothing new. Arguably, that’s what managers (and management consultants) were designed to do. But new opportunities to track employees proliferate every year. Old-fashioned watches are being displaced by ‘quantified self’ trackers that decode our days into data points. These technologies prompt a new HR question: should employers track their employees with new tools?

How companies answer this question says a lot about about their management approach and their company culture. We explore employee monitoring from the perspective of employees and employers. We talk to two founders of quantified-self-style companies who argue that businesses shouldn’t track employees—at least, not individually. And we consider some arguments for how companies can (tentatively) embrace monitoring, without being too creepy.

Against the clock: monitoring the wrong things

The oldest and most pernicious employee monitoring technology is the clock. The 8-hour day, or 9-5 grind, places a standard expectation for when employees work—and, often, where they should be. But, it’s a flawed measurement, because it focuses on quantity instead of quality. The 40 hour work week is an inherited norm, not a magic number. In theory, results should matter more than time. If employees could deliver superior results in less time, everyone would be better off. But that’s not how the corporate world works. Despite ample evidence that work hours have an inverse relationship with productivity, many managers erroneously equate facetime with work quality.

A few years ago, Robby Macdonell, the co-founder and CEO of RescueTime, harnessed his 9-5 frustration into a new kind of time management technology. He was inspired to code a simple AppleScript to account for the hours he was putting in at work.

I’d look up at the clock a 5pm and think, “that doesn’t look right – that many hours couldn’t have passed—what was I doing with my day?” I’d scan back to see what I had to show for the time I put in. The output didn’t seem to match up with what I thought I’d be able to get done with those hours. It was easy to assume that I must have been wasting a lot of time.

Robby’s AppleScript evolved into a company. Now anyone can download RescueTime to see where they’re spending their screen time. Often, people are surprised by their results. According to Robby, many people are scared of tracking their time because they “don’t even want to know” how much time they spend on Facebook or Reddit. But in his experience, after a few weeks’ worth of time-tracking, most people realize they aren’t spending half as much time on their guilty-pleasure site of choice as they thought they were. Instead, they’re sinking a lot of time into email, Slack and other kinds of communication tools.

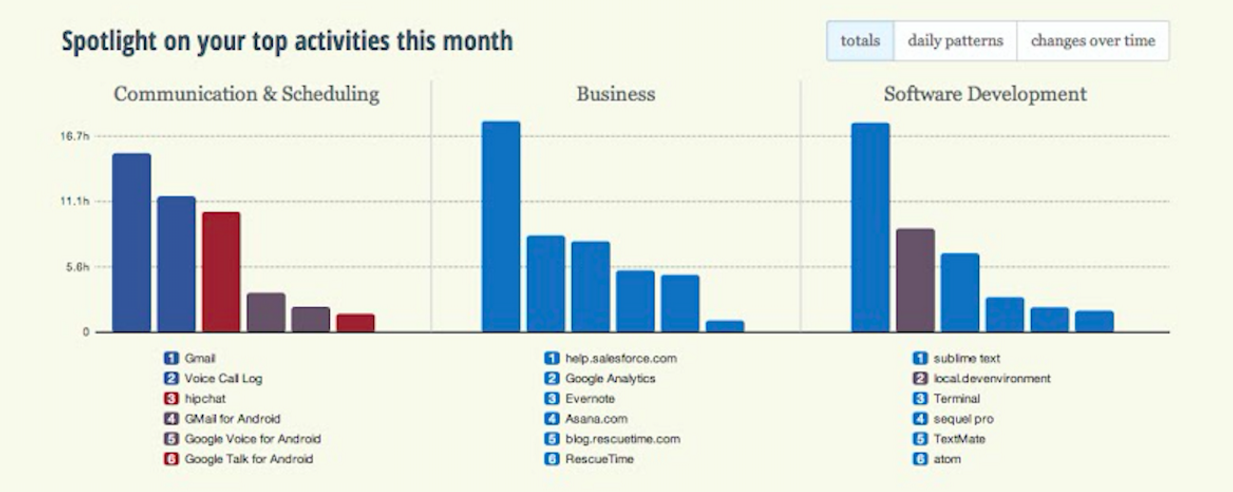

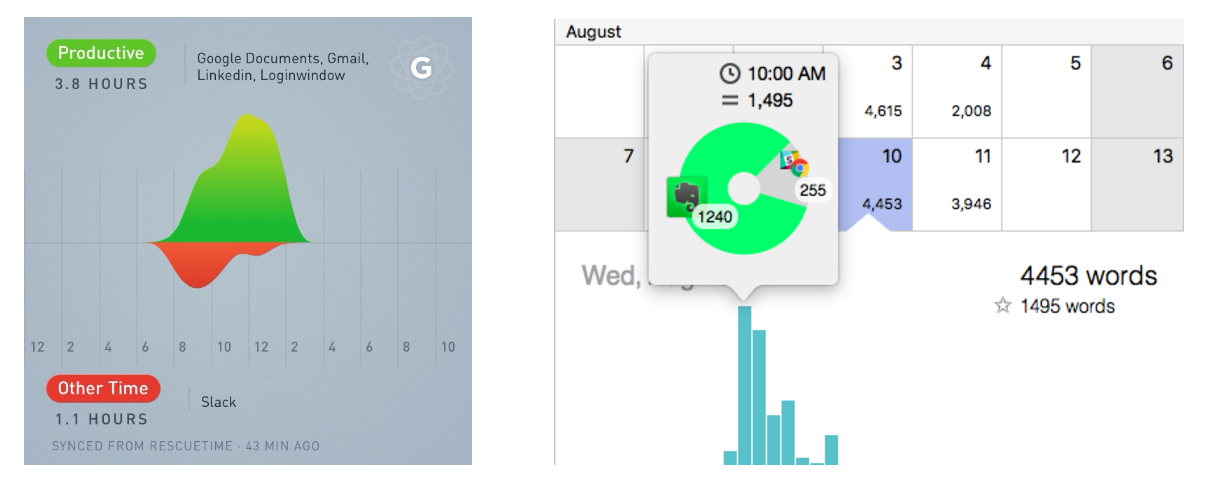

Here’s an example of one user’s month of time tracking data. This user deems blue time productive, grey time neutral and red time unproductive. (Each user can classify different activities as productive or unproductive.)

And here’s a more granular view of where they were spending their time:

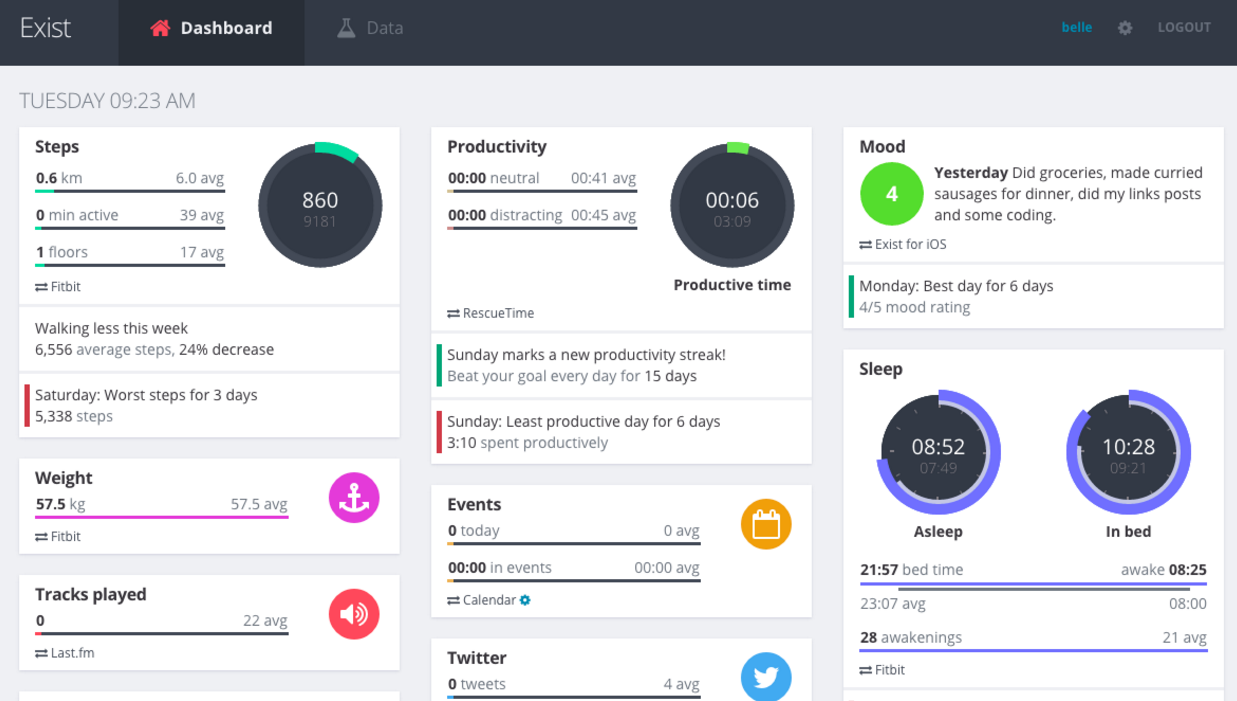

Employee monitoring for employees

RescueTime is one of the many ‘quantified self’ tools that can give workers new ways to measure their own work lives. Another is Exist, a service that compiles multiple self-tracking services into one, centralized view. It marries productivity data from RescueTime and Todoist, local weather reports from Forecast.io, songs played from Spotify and Last.fm, users’ self-reported mood logs, social media posts from Twitter and fitness tracking data from Fitbit, Withings, Runkeeper and other fitness apps.

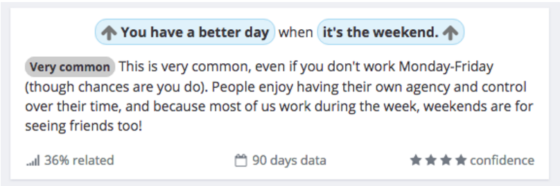

After a couple of months, Exist can identify correlations in users’ data and reveal what matters to them. According to Josh Sharp, the co-founder of Exist, these correlations are often unsurprising: “Monday is one of the least happy and least productive days of the week for everyone—people just don’t want to go back to work.” People are also more productive when they sleep more and are usually happier on the weekends.

Exist also offers users benchmark data comparing them to other people on the platform. According to Exist’s benchmarks (based on aggregated RescueTime data), the average user clocks in a whopping 2 hours and 34 minutes of productive time a day. If that number sounds low, consider that Exist users are a self-selecting group who are interested in maximizing their productivity and tracking their performance. The benchmark could be considerably lower for the average office worker.

“It’s amazing how much of a work day can be taken up by things that aren’t actually productive” says Josh. He also notes that people tend to be more productive when they listen to more music.

“Personally, I think the big relationship we find between listening to music and productivity is a product of so many people needing to block out the harmful, distracting background chatter of an open-office plan.”

Of course, correlation doesn’t mean causation. Nevertheless, it’s interesting to see your own correlations. It can also be useful to track different kinds of output data, like the number of words you write, if you’re a writer, or your number of Github commits, if you’re a coder (which Exist also collects). Tools like Word Counter, Asana, Trello, Zapier, IFTTT, Gyroscope and RescueTime can work in concert to arm employees with information about how they’re working. If so inclined, you can use this kind of data to help manage yourself and understand what works for you. But, as with any kind of data collection, it’s going to have its limitations, the number of words you write, or emails you send are easy to measure—but they mightn’t actually be important. Quality can be hard to quantify.

Employee monitoring for employers

Some employers argue that employee tracking is fair game—most companies get their employees to sign fair use agreements that explicitly acknowledge that employees shouldn’t assume privacy when they’re using work devices. But from many employees’ perspectives, desktop monitoring, keystroke logging and other kinds of tracking are intrusive and paternalistic.

Robby and Josh both agree that employees can learn a lot from self-monitoring, but that businesses shouldn’t get too Big Brothery. Josh worries that comprehensive employee activity tracking can further blur the line between employees’ work and personal lives. And, according to Robby, individual employee monitoring can cross the line between management and micromanagement very easily. Robby thinks things get particularly fuzzy when companies use fitness tracking leaderboards to motivate employees to move more; “it can feel like you’re trying to tell your employees how much they should exercise, and that just sounds kinda gross.” He also argues that:

“It’s a little myopic to think that a tool that helps you understand your screen-time should only be focused on maximizing your productivity with that screen-time. We can benefit from understanding our relationships with our devices, regardless of whether or not we’re trying to maximize our productivity all the time.”

Endorsement, not enforcement

Employers needn’t shy away from employee tracking altogether. Both Robby and Josh agree that opt-in, anonymized and aggregated tracking could be useful for employees and employers alike. For example, it could be good for HR departments to know that certain teams, or departments, are sinking an inordinate amount of time into meetings. That’s a cultural problem that could benefit from an HR (or executive management) intervention. RescueTime is launching a beta-version of its platform for this very purpose.

But, when it comes to individual employees’ work habits, it’s best to leave the tracking, and managing, to each person individually. Giving employees access to tools to help them manage themselves is the safest first step:

“Companies should encourage their problem solvers (who they’re already paying to solve problems) to be good at solving their own problems. Doing that in a data-driven way can be really helpful.” – Robby Macdonell

“Companies that want to boost employee happiness should look at existing research and be willing to implement big changes that give employees more autonomy to direct their own work days.” – Josh Sharp

Individuals know what works for them. If companies hire the right people and give them clear, measurable goals, they should be able to trust employees to manage themselves. That trust can take the form of endorsing self-monitoring tools, offering more flexible remote work options and welcoming discussions about what kinds of work environment, work hours and performance metrics matter to each employee.

Ultimately, empowering employees to take control of their own workdays is a lot more revolutionary than using the latest employee monitoring tools. It flips traditional management on its head. It’s based on trust. And it treats employees like adult humans. But companies need to be ready for the results: it might just become obvious that offices, 40 hour work weeks, meetings and management offsites are thoroughly useless. And employees could be well-armed with the data to prove it.