Understanding the gig economy

The future of work is clouded by two contrasting visions. One is a daydream with a laptop and a sea view, where highly-skilled work is divorced from any particular location. The other is a nightmare of drudgery, where hours are spent plodding the corridors of a giant warehouse pushing a trolley with a robotic earpiece telling us to walk further and faster. Both visions take their cue from the excitable narratives swirling around the “gig economy” an idea for which there is no simple, commonly agreed definition.

To some it means white collar piecework, to others the wild west of unregulated digital sweatshops. The Undercover Economist, Tim Harford, refers to it as “tiny amounts for tiny jobs” which doesn’t feel adequate when others are describing a connected work marketplace whose value could soon run to tens of billions of dollars.

The Human Cloud

Gigging itself has its roots in the 1920s jazz scene but its current revival is more digital than musical. Mckinsey, so often the source of excitable business language, offers the most sober definition, calling it “contingent work that is transacted on a digital marketplace.”

For its boosters, the gig economy is the beginning of “the human cloud” where employers will be able to overcome skills shortages and liberate themselves from the confines of location. The loudest of these voices are coming from the platforms on which this economy is being constructed, like MBAandCompany, whose CEO Daniel Callaghan recently told the Financial Times: “You can now get whoever you want, whenever you want, exactly how you want it,” he says. “And because they’re not employees you don’t have to deal with employment hassles and regulations.”

The development economist, Guy Standing, sees something altogether different. He has coined the term “precariat” (an unhappy marriage of the precarious and proletariat) to describe a new and expanding underclass. While most economists have fretted about jobless growth since the last financial crisis, Standing looks to the future and sees “growth-less jobs” as the real issue. He foresees the spread of low productivity jobs with basement wages and practically no benefits like health insurance or pensions.

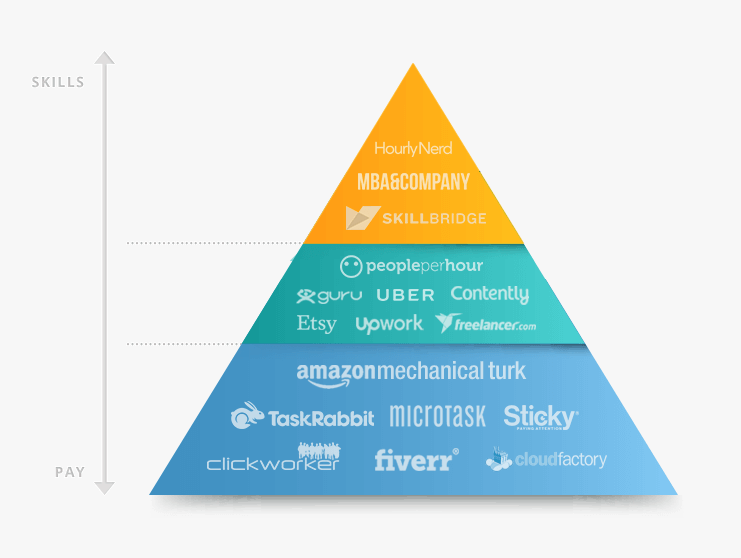

In short, the gig economy is an idea that tends to reflect the prejudices of its observer. A quick look at its emerging hierarchy gives some perspective.

The most solid thing you can say about the gig economy is that it’s smaller than the hype surrounding it. The prominence of companies like Uber, whose fleet of drivers are not employees, and the giant digital lawn sale that is Etsy, where people can turn handicraft hobbies into a side income, has caught the public imagination. The gig economy has already featured in the US election cycle with Democrats attacking it from the left and Republicans lauding it from the right.

Showing up everywhere but the data

But a thorough examination of government data shows little has changed in the last decade, with the percentage of Americans declaring themselves self employed declining. Some 6.5 percent of America’s 157-million-strong workforce were self employed in 2015, down from a high of nearly 9 percent in the 1990s. The proportion of workers with multiple jobs is equally stagnant.

Across the pond in Britain, freelancers make up just 2 percent of the workforce, a figure that is largely unchanged in the last 15 years. It’s possible that the increase in the number of Britons declaring themselves self-employed may contain some gigsters but it could also be explained by more traditional forms of self-employment. The three growth areas in UK self employment are hairdressing, cleaning and management consultancy. Yes, it’s possible that some of these consultants are trading their services on HourlyNerd or one of its competitors but these sectors were growing before anyone said “gig”. Conversely numbers of self-employed taxi drivers are in decline. As Lawrence Mishel, president of the Economic Policy Institute puts it: “evidence of an exploding gig economy is showing up everywhere but the data.”

Related: How to hire freelancers

When it did show up in the data it was a false alarm. Most sensible analysts are agreed that when the wonks at the US Governmental Accountability Office announced in 2015 that the percentage of contingent workers had leapt from 30.6 percent in 2006 to 40.4 percent, it didn’t mean much. Their methods were problematic and their definition of contingent work was so broad it included everyone not in full-time conventional jobs.

The revolution will not be declared

The obvious thought is that official figures are a bad place to go looking. Not everyone declares gig income, especially if the work is done alongside a traditional job. Many people don’t think of renting out their couch or their car as a form of paid work, so they don’t tell census workers about it, let alone the tax collector.

A fairer assumption is that the gig economy is in its infancy and that its growth won’t be linear. The big beast of this emerging economy, Upwork, is cited as evidence of this: the human cloud platform took 10 years to reach $1bn revenues but expects to grow those ten-fold in the next six years.

To rebut the skeptics, economists like Harvard’s Larry Katz have dug into ‘1099’ filings for evidence. When a business, non-profit or government agency pays someone more than $600 a year in non-employee compensation this is the form they file with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). These filings are on the rise. A deep dive into government data finds that non-employer businesses (sole proprietors) are up from 12 percent of the US workforce at the end of the 1990s to 16 percent in 2013 (no data since). This has prompted some observers to argue that we have a “1099 economy”.

Daniel Tomlinson, from the Resolution Foundation in London, says that: “measuring the gig economy isn’t easy and governments would do well to follow the example of the US Department of Labor who have announced that they will soon be collecting statistics on the status of contingent workers.”

But he cautions against overstating the changes in the labor market and the extent of contingent working: “This isn’t to say that the gig economy is going to stay small; adoption of new technology by existing businesses, disruption by new innovative firms and the National Living Wage are all likely to contribute to the growth of the gig economy in the years ahead.”

21st Century laws

So the rise of the gig economy is real, it’s just not as large or as rapid as some have suggested. But it does pose very real challenges to business and policymakers. We’re seeing the most obvious manifestation of this is the legal battles being waged against Uber. Are their drivers employees or not? The company says absolutely not but some of the drivers take the opposing view.

This is where the work of Alan Krueger, formerly an economic adviser to President Barack Obama and Seth Harris from Cornell University come in.

“There is currently much uncertainty as to whether your Uber driver — or Lyft driver, or TaskRabbit handy man, or Thumbtack personal trainer — will be judged an employee or independent contractor by the legal system,” writes Harris.

The Krueger-Harris answer is to create another category of worker in the gray area between “employee” and “independent contractor” called “independent worker”. Their proposal would allow gig workers to join or form a union but it wouldn’t entitle them to paid holiday or protection from being fired. It would enable firms like Lyft to offer health insurance or pensions as benefits without the worry that the courts would label them employers.

The cynics will rightly wonder how many of the sharing economy behemoths would really want to offer benefits unless legally obliged to do so. Meanwhile, the first job ads have begun to appear for C-level Chief Freelance Relationship Officers. A recent Randstad talent report found that nearly half of HR leaders were thinking about how to respond to the gig economy.

HR expert Mervyn Dinnen says that freelance relationship officer is “a role whose time has come” and foresees more attention being paid to the way companies manage their reputation among freelancers. The Freelancers Union and their #FreelanceIsn’tFree campaign have already shown how gig workers can make themselves heard and gain traction. Our world of work is being reshaped but its final form will be contested.